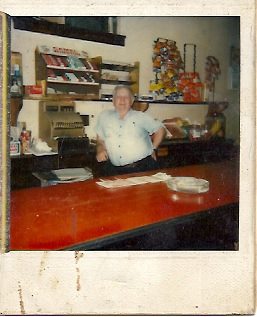

The store front window was coated in decades worth of coal soot. It was a deliberate aesthetic. Upon entry patrons were greeted with warped clapboard floors, smoke tinged paint that bubbled and cracked and two scales that for a penny would tell your weight and fortune.

Seven days a week my granddad, Skomie, could be found perched behind the long red formica bar, reading the paper and smoking a cigar as a baseball game blared in the background. I was a fixture in my granddad’s bar from before I could walk. Most afternoons, I would hop off the school bus and walk it so that I could empty ashtrays and fetch ice cold cans of Coors and Budweiser for the old men who stopped in every day. The regulars had their favorite stools, as did I. The one closest to the door. It was the fastest spinner.

My granddad’s bar was officially called “The Sports Center”, but there were no signs announcing its name and everyone just referred to it as “The Place”. Skomie was a gruff, insensitive, first generation Russian immigrant and a Korean War veteran. As a teenager, he spent one summer extracting coal from the full bellies of the West Virginia mountains before declaring that the next time he wanted to go underground was when he was good and dead.

So, he opened a bar, a bar that was cover for his real money maker. Skomie was the town bookie.

In the evenings, right before my granddad would place his calls to his mysterious friends in Cleveland, my grandmother and I would carry a saran wrapped plate of steak, fried potatoes and pork and beans to him from our apartment that was just a couple hundred yards further down on the main street of our small town nestled deep in the bosom of the Appalachians.

Most nights, I would grab a glass bottle of Coke from the cooler and a Snickers from the counter before settling in to the small table in the back where he ate his dinner. We listened to the police scanner and watched the large rats scurry along the banks of the polluted Tug River. On evenings that he was busy, I would use the disabled beer taps to serve my imaginary friends drafts during my interpretation of a tea party. I would slide their mugs to them, shake my head and say, “I’ve seen better head on a beer”.

I kept my pink and white bike complete with it’s flowered basket and sparkly streamers parked at The Place. Between the lunch and evening shifts, Skomie would lock up the place and take me go to the big municipal parking lot behind our bar to help me practice my bike riding skills.

When I became a more confident biker, I would navigate the busy downtown streets to either pick up money someone owed my granddad or deliver money he owed them. The money was always in a brown paper bag that I secured in my bike basket. My mom had had the same job when she was younger. She said that she always skimmed a couple of bills off the top because she knew that there was an honor code and they rarely counted it. I did not know this and even if I had I have always been way too lawful and guilt-ravaged to even think about doing that. I just smelled it.

The Place only closed three times a year. In July for three-four days during the MLB All-Star break. We would either go to Florida or to visit my uncle in Nashville. It was closed for one day in August so we could attend the WV State Fair and the week following the Super Bowl when my grandparents went on their annual cruise; a tradition they continued to go together even after they divorced.

I once asked my granddad who he was cheering for in the Super Bowl and he said, “Sosha, my dear, I’m cheering for the team that puts the most food in our bellies. You never, ever gamble with your heart. That’s a fool’s bet and we’re no fools.”

We didn’t cheer for a certain team but we did cheer for the spread. My granddad taught me to read the spread and what the over/under meant at a young age. He called it a math lesson and told me that math was always better than emotion.

I am sure that Child Protective Service would lock someone away faster than you could say, cover the spread, if there was a five year old serving up Pabst Blue Ribbon in a gambling den today. However, just as the smell of apple pie or spaghetti sauce will remind many of their grandparents, I will always be reminded of mine when I walk into a dive bar and inhale the sweet scents of cheap beer and regret.

That’s when I go home.

Its raining out side so I set down to read some of your stories. This one has a lot of my memories as a kid at the place with with your granddad, the brown bags, the stake dinners, his watermelon parties when John was playing ball. I could see Skomie as clear as day, hear him laugh and the smell of his cigar. Good story