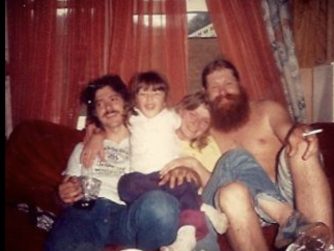

I waited on my mama to make her appearance at our annual Memorial Day family reunion with a nauseating mixture of need, anxiety and dread. When she arrived, I blinked and shook my head like a battered boxer in an attempt to adjust and refocus her.

It was a clear, warm day in May, but my mom looked like a November Jack o’ Lantern; sunken, yellow and extinguished. Her ill-fitting bibbed overalls were childlike, but her face, wrinkled and pockmarked, was old and tired. Her hair was thin and stringy and her dry and cracked hands shook as she lit one Native Spirit cigarette after another.

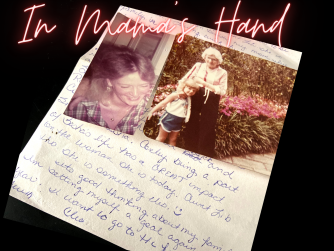

Her appearance that day was in stark contrast to the woman who upon entry to this world was aptly named Starr. She was no longer the beautiful person with the bright blue eyes that twinkled and danced like lightning bugs in a summer sky nor was she the mom whose mega-watt smile would spread across her face when she hugged me and whispered, “I sure do love you, So-So!”, in my ear.

That’s the mama I have frozen in time in framed pictures smudged with my fingerprints from where I try to feel her one more time.

My mama was sick. My mama was dying.

However, my mom’s illness didn’t come with brightly colored lapel ribbons or 5Ks to raise money for a cure. When my mom was in the throes of her disease, people certainly didn’t bring casseroles and pound cakes to take some of the burdens of life off of us.

That is because most people, including me, believed that she chose her sickness.

It was her choice to snort lines and shoot up her veins over helping me with my homework or going to my volleyball games. It was her choice to love Tylox, Dilaudid and heroin more than my brother, sister and me.

It was her choice to be a drug addict.

It is easy to understand why I thought that not choosing drugs was simple. I grew up in the ’80s when Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign was ubiquitous.

Until recently, substance abuse was seen as a disease of choice or a lack of control; one that only affected criminals and degenerates. However, in 2016 Dr. Vivek Murthy, the U.S. Surgeon General, released “Facing Addiction in America”, a landmark 400 page report that states that addiction is a chronic brain disease; not a moral flaw.

This is a lesson I needed to learn about a subject I considered myself an expert. I needed to learn this so that I could forgive her – and, so I could forgive myself. It wasn’t my job to save her. It was okay that I learned to protect myself from her.

I spent years believing that my mom simply chose to be a drug addict; that she loved opioids more than me. I don’t believe that anymore. However, that doesn’t make the years of embarrassments, poverty, and abuse go away. What was going on with her was a disease, but that doesn’t take away the fact that her disease made her untrustworthy, disloyal, and just plain mean. Those are valuable lessons that her addiction taught me as well.

Through my mom’s struggle with addiction and its aftermath, I have learned what is really important. For years it made me skeptical and cynical of nearly everyone. I was certain that everyone would end up hurting me – that loving people only led to heartbreak. I know that is not true. I have learned that I can be empathetic to a wide array of people, while still being selective in who I put my time and energy into. I know that forgiving someone doesn’t mean that you have to have them in your life because you get to set the standards for what you need in your relationships.

I have learned that even though the big, gaping, bleeding wound of her has healed, that the jagged puffy scar will remain. I can remember all the physical pain and mental anguish that she caused me and I can also remember how I thought the sun paled in comparison to her warmth. Forgiving her was a gift to me and so is remembering. I know that even when you can grant grace to the reason that someone does something, even when you can forgive them, it may not mean that you can have them in your life. Sometimes the lesson that you learn is that when the hurt and the betrayal are from the one you should have been able to trust the most, that forgiveness and proximity don’t necessarily have to coexist.

This is, perhaps, the hardest lesson of all to learn – how that you can, in time, forgive while also understanding that forgiveness doesn’t erase the pain from the damage caused.

I know that if she were still alive, I probably couldn’t have my mom in my life. I just wish that I would have had a chance to tell her that I never stopped loving her, and that I never gave up hope that she would one day be that golden woman who made my soul dance.

I have to hope that is a lesson she learned.