My cell phone rang when I was on my way to the hospital to meet my nephew. It startled me. I was concentrating on navigating the winding mountainous roads of my home state, West Virginia, and I was surprised that I had reception. I was even more surprised by the voice on the other end. It was my brother-in-law. I took a mental note that this was the first time we had ever spoken on the phone. I immediately broke out into a cold sweat fearing that something had happened to my sister or nephew—sadness and death was the kind of s**t my family was known for.

I quickly spit out, “Hello? Hello? Angie ok? The baby?” He replied in his lulling, deep drawl, “Sosh, Sosh, they are just fine. Well, your sister is meaner ’an a rattlesnake right now, but that ain’t nothin’ new, right?” He giggled at his accurate joke and exhaled cigarette smoke. “Now, listen, they fine but Ang told me to walk outside and call you. She wanted to let you know your daddy is up here at the hospital.”

Now it was my turn to giggle. I hadn’t called the man dad in almost two decades, and I certainly had never referred to him as daddy. My brother-in-law graciously ignored my bitter laugh. He didn’t add anything like, Please don’t come up here and make a damn fool of yourself, leaving me to deal with my tired, overwhelmed wife on the day our son was born. It was implied. I ran up to the maternity floor and texted my husband: My “daddy” is here. I’m SO glad Conley’s not with me. His reply: It’s ok. Stay calm. You can do this. Conley’s great…mom and dad are plowing her with sugar. I smiled knowing my daughter was safe and happy with her daddy and the only grandparents she had ever known.

When the doors slid open, I took a couple of deep breaths, inhaling antiseptic and the nurses’ leftover Chinese and McDonald’s lunches. I silently repeated my husband’s advice. It’s ok. Stay calm. You can do this. It’s ok. Stay calm. You can do this. I plastered on my best fake smile as I entered the room. There he was. Daddy.

I didn’t acknowledge him. I walked directly over to my sister and hugged her. I then awkwardly wedged myself between the food cart, with the untouched scrambled egg breakfast and some discarded gossip magazines, and balanced myself on the edge of her small bed. There was a perfectly good seat available next to my father. I needed to be behind a barricade.

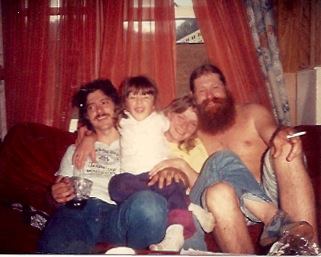

It had been more than two years since I had seen my father. At that time I was pregnant. He had ambushed me when I stopped by my grandmother’s house. There had been a traitor; someone had told him I was visiting. When we pulled up, he came running out of the house and attempted to hug me. I flinched. He tried to touch my stomach—with his dead hand.

When I was 12, my dad’s right hand was mangled in a commercial fishing boat accident, one of the few legitimate jobs he ever held. He chose to keep his hand rather than get a prosthetic. The thumb was cut off, the fingers were fused together at an awkward angle and the hand quickly atrophied. It creeped me out.

As he reached out, I threw my hand over my protruding stomach, jumped back and shook my head no. Emphatically no. He was not going to infect the perfect creature growing inside me.

I stomped up the steps to mndmother’s house. Bristling. He followed closely behind.

He asked if he could talk to me privately. We stepped into gran’s bedroom, strewn with her ever-present piles of clean laundry. He asked me, “Why do you hate me so much?”

“I don’t even know you. You’ve barely been part of my life. And, let’s face it – when you were around it was pretty sh***y. You’ve never done anything for me and you don’t just get to decide that you want to be part of it now that I have clawed my way out and put together a pretty good life.”

“Well, Sosh, I was in prison. A lot.”

“Holy s**t! Is that your excuse? You aren’t Nelson f***ing Mandela! Yep, you’re right. You were in prison. A lot. Let’s see: when I was born, when I graduated high school and when mom died. You were a junkie and a below average drug dealer who got caught. A lot.”

He shook his head, “You and me are a lot more alike than you know.”

I snarled, “You don’t know a g*dd**n thing about me. We are nothing alike. Not one f***ing bit.”

When we were reunited in that hospital room two years later, I was determined to not make the same kind of scene for my sister’s sake. However, as I sat there, I realized that for the first time in years I felt something other than pure, unadulterated hatred for the man. On this day, I felt pity.

He was a broken down ex-con with a raging opioid addiction, but he dressed like a suburban middle-aged dad. Khakis, tucked in button-down, white New Balances. He worried an ill-fitting hat. Took it off and nervously ran his good hand through his still-thick, wavy hair. The man had always been vain about his hair. Admittedly, this was a quality we shared.

I felt bad for him even though I knew he was high off his tree. I can spot when someone is high at 100 paces. It is my superpower. However, when I mentioned wanting a cup of coffee he perked up and excitedly offered to get me a cup. I may not have felt black hate for him at that moment, but I still wouldn’t accept even a putrid cup of hospital coffee from him.

After a few minutes, he started to nod off. When he started snoring, my brother-in-law, sensing my sister’s embarrassment, shook him and asked him if he wanted to go home and get some sleep. He apologized and shuffled out, balancing his own styrofoam cup of coffee in his mangled right hand.

As he was leaving he noticed the pictures of Conley that I had brought my sister. He sheepishly asked for one, and I reluctantly gave it to him. He said, “She has Tony’s eyes, but she has our face.”

Our face? Our face.

He was right – she does.

As he was leaving he looked over his shoulder and said, “Thanks for speaking tomorrow, Sosha. I know you’ll do a good job. I wish it was me and not him.”

“I do too, Steve.”

As I eulogized my baby brother the next day, I spotted Steve in the crowd of mourners. He wasn’t invited to sit with our family on the front row. He sat alone in the middle and sobbed..

After the funeral we invited everyone, including Steve, to my aunt’s house so that they could tell us how sorry they were that we had just buried my beautiful, kind-hearted 21 year old brother as they heaped paper plates full of ham rolls, pasta salad and pound cake.

My husband and I stood at the counter moving food around on our plates, grateful for the six-pack of Michelob Ultra I had found in the back of the extra fridge. There are a few times that you are grateful for Michelob Ultra. That was definitely one of those times.

Steve quickly saddled up to the kitchen table with his plate and coffee. I didn’t offer him a beer. He chatted with with one of my grandmother’s friends and told him about the anguish of losing a child, about his commercial fishing “career,” and how he lost his hand.

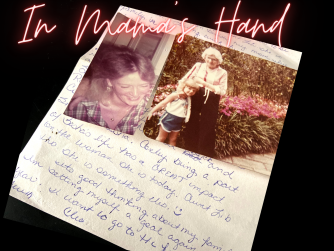

The old man had never met Steve before and nodded at him sympathetically. I thought about telling the man how Steve had still been able to beat my mom with his good hand, how he had spent much more time in prison than he had on a commercial fishing boat and how I achingly wanted it to be him in the cold November ground. But, I didn’t. I was weary. Bone tired. I just watched as he ran his good hand through his hair, shook his head a little. A habit leftover from when his hair hung down his back, I assumed.

After I had collected a couple dozen apologies and heavily perfumed hugs, I told my husband that it was time to go. I desperately wanted to be between the familiar and safe walls of my in-laws, needed to hold my daughter, kiss her face, smell her hair.

We got in the car and I immediately kicked my high heels onto the floor mat. Breathed out.

Tony let the car warm up for a minute. After he put the car in gear, he slid his hand over and squeezed my knee. He told me how proud he was of me and how much he loved me.

As we pulled out of the crowded driveway he added, “Well, you can say one thing for ole Steve. Old man has the prettiest goddamn grey hair I’ve ever seen.”

The first genuine smile I had had in days spread across my face. Before we turned onto the main road, I started laughing. Deep, rolling laughter. I lost my breath and tears streamed down my face.

I cried. I lost my breath.

Then I opened the visor mirror. Wiped my mascara.

Ran my hand through my hair, shook my head a little.

* This article originally appeared in MUTHA Magazine and is reprinted here with permission.

Emotionally riveting.

Just. So. Good!